Tuesday, December 9, 2008

Wednesday, December 3, 2008

Wednesday, November 19, 2008

Wednesday, November 12, 2008

Tuesday, October 21, 2008

Tuesday, October 14, 2008

Monday, October 13, 2008

Monday, September 22, 2008

Friday, September 19, 2008

Wednesday, September 17, 2008

Wednesday, September 10, 2008

Sunday, September 7, 2008

Ericsson-The Ways We Lie

Friday, September 5, 2008

Argument

Argument

ambiguity - A statement with two or more meanings that may seem to exclude one another in the context.

There are two types of ambiguity, lexical and structural.

Lexical ambiguity is by far the more common. Everyday examples include nouns like 'chip', 'pen' and 'suit', verbs like 'call', 'draw' and 'run', and adjectives like 'deep' and 'dry'. There are various tests for ambiguity. One test is having two unrelated antonyms, as with 'hard', which has both 'soft' and 'easy' as opposites.

Structural ambiguity occurs when a phrase or sentence has more than one underlying structure, such as the phrases 'Tibetan history teacher', 'a student of high moral principles' and 'short men and women', and the sentences 'The girl hit the boy with a book' and 'Visiting relatives can be boring'. These ambiguities are said to be structural because each such phrase can be represented in two structurally different ways, e.g., '[Tibetan history] teacher' and 'Tibetan [history teacher]'

anecdote - a usually short narrative of an interesting, amusing, or biographical incident

appeals – ethos, logos, pathos (see handouts)

concession - when you show an audience that you have anticipated potential opposition and objections, and have an answer for them, you defuse the audience’s ability to oppose you and persuade them to accept your point of view. If there are places where you agree with your opposition, conceding their points creates goodwill and respect without weakening your thesis.

deductive – Deductive reasoning works from the more general to the more specific. Sometimes this is informally called a "top-down" approach. We might begin with thinking up a theory about our topic of interest. We then narrow that down into more specific hypotheses that we can test. We narrow down even further when we collect observations to address the hypotheses. This ultimately leads us to be able to test the hypotheses with specific data -- a confirmation (or not) of our original theories.

inductive - Inductive reasoning works the other way, moving from specific observations to broader generalizations and theories. Informally, we sometimes call this a "bottom up" approach (please note that it's "bottom up" and not "bottoms up" which is the kind of thing the bartender says to customers when he's trying to close for the night!). In inductive reasoning, we begin with specific observations and measures, begin to detect patterns and regularities, formulate some tentative hypotheses that we can explore, and finally end up developing some general conclusions or theories.

logical fallacies (ad hominem, begging the question etc.) – see your handout

syllogism - In a syllogism the primary premise is a general statement. The primary premise is always universal, and may be positive or negative. The secondary premise may also be universal or particular so that from these premises it is possible to deduce a valid conclusion.

Everything that lives, moves (primary premise)

No mountain moves (secondary premise)

No mountain lives (conclusion)

enthymeme - An enthymeme is a partial syllogism. It is based on the probable rather than positive premises and is based on implicit conjectures that are shared by the speaker and the audience. The speaker gives the primary premise and assumes that the audience will supply the missing knowledge in order to reach the conclusion.

Everything that lives, moves (primary premise)

No mountain lives (conclusion)

FALLACIES

Fallacies are defects that weaken arguments. Fallacies can be quite persuasive, at least to the casual reader or listener.

Tuesday, September 2, 2008

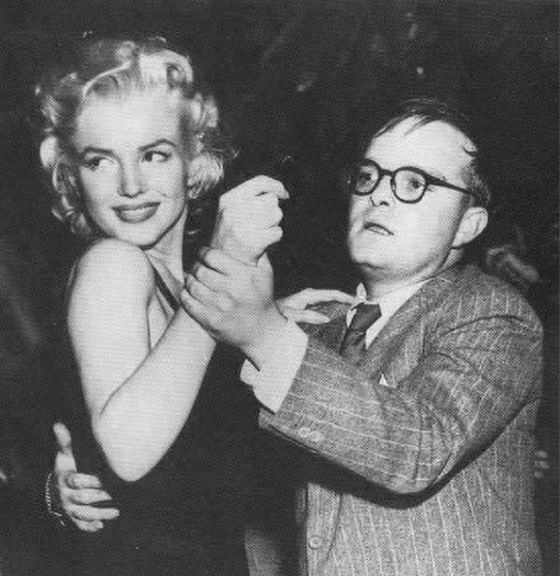

A Star is Born?

Monday, September 1, 2008

Thursday, August 28, 2008

Wednesday, August 27, 2008

SOAPSTone and Rhetoric Terms

HW: Review for quiz tomorrow on the following terms:

SOAPSTone

Anadiplosis: occurs when the last word in a sentence, clause, or phrase is repeated at the beginning of the next sentence, clause, or phrase.

Ex. “They call for you: the general who became a slave; the slave who became a gladiator; the gladiator who defied an Emperor.” – Gladiator

“Our time has come. Suffering breeds character; character breeds faith; in the end faith will not disappoint.” Jesse Jackson, 1984 Democratic National Convention

Anaphora: Repetition of the same word or phrase at the beginning of lines, clauses, or sentences.

Ex. This royal throne of kings, this sceptred isle,

This earth of majesty, this seat of Mars,

This other Eden, demi-paradise.

Shakespeare, Richard II

Anastrophe: Inversion of the usual word order in a sentence or parts of a sentence.

Ex. A promising Jedi, you are. - Yoda

Asyndeton: Omitting connecting words, usually conjunctions, between clauses.

Ex. We laugh, cry, scream, shout.

Polysyndeton: Adding connecting words (conjunctions) between clauses for effect.

Ex. We laugh and cry and scream and shout.

Epanalepsis: Beginning and ending a clause or sentence with the same word or words – a circular sentence.

"Common sense is not so common." - Voltaire

Epistrophe: Repetition of the same word or phrase at the end of lines.

Ex. I do not like dogs. When did I ever say I like dogs? And why would you possibly buy me a dog?

Thursday, August 21, 2008

DAY 4

Wednesday, August 20, 2008

DAY 3

Tuesday, August 19, 2008

DAY 2- PATHOS, ETHOS, LOGOS

APPEALING TO YOUR AUDIENCE

Audience: The audience is the writer's targeted reader or readers. The relationship between the writer and the audience is critical. You should consider the kind of information, language, and overall approach that will appeal to a specific audience. Here are some questions to ask yourself during the prewriting stage of writing your persuasive essays:

Who exactly is the audience?

What do they know? Believe? Expect?

Will the audience disagree with me?

What will they want me to address or answer?

What type of language will I use? What type of evidence?

What strategies will I use to convince them?

PATHOS - EMOTIONAL

Arguments from the heart are designed to appeal to audience’s emotions and feelings. Emotions can direct people in powerful ways to think more carefully about what they do. In hearing or reading an argument that is heavy on emotional appeals, ask yourself these questions: How is the speaker or author appealing to the audience’s emotions? Why? Always try to name the emotions being appealed to (love, sympathy, anger, fear, hate, patriotism, compassion) and figure out how the emotion is being created in the audience.

Emotional appeals are often just examples - ones chosen to awaken specific feelings in an audience. Although frequently abused, the emotional appeal is a legitimate aspect of argument, for speakers and authors want their audience to care about the issues they address. This is most useful with a sympathetic audience.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-AqlLyLeJuQ

Here are some, but not all, techniques that are used in this type of appeal:

• Include an anecdotes-- a moving story that prove your opinion

• Use emotional language or “catchy words” or language that involves the senses to appeal to people’s values or guilty consciences.

• Include connotative language -- the suggestions, associations, and emotional overtones attached to a word

Where do we see this in the Sanders essay?

• Include a bias or prejudice. Omitting or not using information that may conflict with or weaken the author’s opinion.

• predicting extreme outcomes of events/dire predication in order to create a sense of urgency

• Use humor

LOGOS - LOGICAL

Loosely defined, logos refers to the use of logic, reasons, facts, statistics, data, and numbers. Logical appeals are aimed at the mind of the audience, their thinking side. Logos can also be arrangement or organization; the author arranges things in a logical order. When a speaker or writer uses logical appeals, he or she will avoid inflammatory language, and the writer will carefully connect its reasons to supporting evidence. This is the most useful appeal with an unsympathetic audience.

Here are some, but not all, techniques that are used in this type of appeal:

• Give logical reasons why your audience should believe you (keep in mind that not all reasons are equally persuasive for all audiences).

• Provide and/or classify evidence that proves or explains your reasons

• Use facts use information that can be checked by testing, observing firsthand, or reading reference materials to support an opinion.

• Use statistics–percentages, numbers, and charts to highlight significant data

• Quote expert opinion––testimony by people who are recognized as authorities on the subject. This is most useful with an unsympathetic audience.

• Cite examples--

• Use cause and effect, compare and contrast, and analogy

• Argue from precedent--this has always been the case.

ETHOS – ETHICAL

Ethical appeals depend on the credibility or training of the author. Audiences tend to believe writers who seem honest, wise, and trustworthy. An author or speaker exerts ethical appeal when the language itself impresses the audience that the speaker is a person of intelligence, high moral character and good will. Thus a person wholly unknown to an audience can by words alone win that audience’s trust and approval. Aristotle emphasized the importance of impressing upon the audience that the speaker is a person of good sense and high moral character. Ethos can also mean fairness; that the author or speaker sees the other side.

This is the strongest appeal.

• Make the audience believe that the writer is trustworthy.

• Demonstrate that the writer put in research time.

• Support reasons with appropriate logical evidence

• Show concern about communicating with the audience.

Analyzing a Rhetorical Situation

SOAPSTONE:

S – Subject

O – Occasion

A – Audience

P – Purpose of speaker

S – Speaker

TONE

Identify these five elements whenever possible to read contextually.

Analyzing a Passage

Consider SLLIDD TOP:

S – Syntax: defining/effective sentence structure

L – Language: type used (refer to ‘language’ words) and connection to audience

(do a SOAPS)

L – Literary devices: metaphor, personification, hyperbole, etc.

I – Imagery: visual, auditory, tactile, olfactory, gustatory

D – Diction: connotative word choice

D – Detail: concrete aspects of the passage

T – Tone: identify specifically/provide a pair of different yet complementary

tones (refer to ‘tone’ words)

O – Organization: movement in the passage between tones, ideas, defining

literary/rhetorical strategies

P – Point of view: perspective of the passage and significance (do a SOAPS)

Frequently, the argument is a combination of appeals.

HW (p. 302): Read Orwell's "Shooting and Elephant" and answer questions 2 and 4. Regarding question 4, you may converse with other members of the class.

Saturday, August 16, 2008

Welcome to Day 1

As you can see, I am a friend of the interweb; as such, I insist on having open and constant communication on the web. We will have quasi-nightly assignments that require you to post on this site. Please be sure to complete these posts during the previous evening. There is a time attached to each post.

HW (p.120): Read Bernard Cooper's "A Clack of Tiny Sparks: Remembrances of a Gay Boyhood." Answer Questions 1 and 2 on the blog.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)